Following on the heels of recent research by Susan Cain (author of “Quiet”) and others, the qualities and strengths inherent to introverts are being increasingly recognized and celebrated. Leaders in a wide range of fields, including business, politics, and the arts, often self-identify as introverts. This may seem surprising, given the stereotype of public figures as extroverts — outgoing personalities who typically crave the spotlight and thrive on social interaction.

Indeed, the parent of one of my students expressed shock when I admitted that I identify as an introvert — “But, you are a performer!” was her surprised reaction to what she saw as a contradiction.

The fact is, some of the very qualities that classify individuals as introverted, are also qualities that enhance their ability to perform well in public.

1. Introverts work well independently. This is extremely beneficial in the practice room, where a strong internal drive and conscientiousness are indispensable. The ability to work independently is also helpful during the long, isolated and sometimes lonely hours of practice that are required of a good performer.

2. At the same time, introverts can also work well in groups, because of their good listening skills and ability to compromise. Sometimes, more-outspoken extroverts are less likely to give equal time to other group members; it is the introverts who ensure everyone feels they have a chance to be heard.

3. They make excellent public speakers and presenters, owing to that same conscientiousness — they come thoroughly prepared!

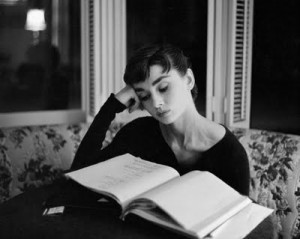

4. Introverts are often subtle communicators, noticing the smallest details and making thoughtful connections that may go unnoticed by others. This can translate to a great range of expression and subtlety in performance. In addition, their love of quiet reflection paves the way for deep and meaningful interpretations.

If you are an introverted sort, I hope that you’ll be encouraged to appreciate these qualities and others that can enhance your performances and above all, to share your abilities.